“By the end of this decade, two in three job openings will require some higher education. Two in three. And yet, we still live in a country where too many bright, striving Americans are priced out of the education they need. It’s not fair to them, and it’s not smart for our future. That’s why I am sending this Congress a bold new plan to lower the cost of community college- to zero.” The bold and determined claim from President Obama during his latest State of the Union address brought many within the Congress to their feet in applause. But at the same time, the plan comes with a fair amount of backlash attached. Questions from opponents are numerous and imploring, and some may just garner a response of “we’re unable to comment on that right now.” So, what does this proposition really involve? Why’s it being proposed now? Who’s in support of it, and why; conversely, who isn’t? Who will benefit from it, and who won’t? What’s the likelihood of the measure even being passed?

What does the measure include?

On January 9th, President Obama rolled out an amorphous proposal regarding the nation’s education system: to make community colleges “… free for responsible students across America.” The question on every American’s mind following this is simply, “How?” The White House proposal, aptly titled America’s College Promise, would have the federal government pay for three-fourths of each student’s tuition, and require the student’s state of residence to throw in the remaining quarter needed. States are also expected to continue to invest in higher education and take up performance testing- with the evidence to back it up- and the community colleges who participate are expected to adopt evidence-based measures to help to improve student outcomes. However, this fee-waiver may not necessarily be free to “everyone”: only students who are enrolled in the school at least part-time, keep a 2.5 GPA, continually make progress towards their degree and are enrolled into transferrable or high-demand programs are eligible. If it were passed, the two years of gratis higher education would provide every high school student with the knowledge that college is accessible, and nearly every party involved concede that high college prices shouldn’t dissuade students from attending.

The plan would also provide further learning for low-income individuals who would have been unable to access such resources prior; something that could prove important if economists are correct in predicting that a large portion of new jobs in the labor force will require- at the minimum- some sort of college education, and credentials such as applied certificates and associates degrees are most often offered by America’s community colleges. A modest investment of approximately $6 billion a year could allow for a more qualified labor force, and in turn result in a substantial payoffs for the economy. Along with this, its community colleges who enroll the largest amount of graduates in the U.S. – about 50% of them- but have their per-FTE (full time equivalent) expenditures are the lowest. But, does this proposal come with more of a cost than a payoff?

Why’s it being proposed?

Obama’s program outline was presented to the public after a time in which state governments- during and after the Great Recession of the late 2000s- lowered the total amount of direct support to higher education systems. Between 2008’s and 2012’s fiscal years, the center for American Progress announced that state funding for college education has dropped from 29.1% in total revenue to 22.3%. If it were to be enacted, this plan could restart state spending on higher education with its idea for a 75/25 split between the federal and state government. Of course, the ultimate goal here would be to assure the president’s vision that community college be “accessible for everyone”. In fact, the Washington Post perhaps best sums up the reasons for it as a “… effort to address income equality and promote American competitiveness.” In fact, leading to the next question many will have:

Will this be beneficial; how much so and to whom? (And in the reverse?)

As the Obama administration outlaid in their fact sheet, the goal is to make “two years of community college as free and universal as high school.” But is this really the case? Well, not necessarily. As has been mentioned, only students who meet the necessary criteria, like keeping a 2.5 grade point average or are enrolled in transferable programs, are eligible. With this fact, this has the potential to create 2 classes of the “ins” and “outs” among uniformly qualified and needy students. Critics also point out that this policy will fundamentally benefit middle-class students who do not qualify for financial aid and do little to help the more destitute, though proponents flip this arguments onto its head and highlight the benefits. Libby Nelson, a writer for the news site Vox, asserted that middle class students are “arguably the biggest winners in Obama’s free college plan” and Atlantic journalist Richard D. Kahlenberg added that “drawing these students in greater numbers to community colleges could strengthen the hand of two-year colleges in state legislatures when it comes to dividing up the higher education spending pie.” And while the proposal is predicted to bring in greater economic gains and could represent a significant and beneficial shift in resource allocations, conservatives still contend that the plan will overstep the federal government’s role in higher education, or that it’s simply another federal entitlement program to be supported by democrats.

Indeed, dissenters do have their valid points when pointing out problems that it has. Historically, trends show that states will disinvest in higher education during economic downturns- which, although we’re recovering, we’re still in- so they may be hesitant to commit themselves to an untenable set-state funding level. Moreso, these required performance-based funding policies will take money out of the state’s pockets, and there’s yet to be any sufficient evidence to prove that these will significantly improve college completion and student outcomes. Research also shows that low-income students are increasingly less likely to enroll in and complete college, and to beat this policymakers will need to find solutions to combat “the inequities” in the educational system.

Another prospective issue is that of Pell Grants- federal grants for low-income undergraduate students who are in need of financial aid. But unlike a student loan, these do not need to be repaid. Again, those who are in opposition to the President’s plan suggest that because these grants are already in place for college students (although the sum is inadequate to cover separate college costs like housing and books), the policy has the potential to channel money to middle- and upper-class community college students who could really afford to go to college without the aid. However, supporters turn this around to say that this 2-years of free college education could help many middle-class families who are stuck in the middle of the road- they make too much money to be eligible for federal Pell Grants, but do not make enough to pay for the total cost of regular college tuition.

What’s the likelihood of the proposal being passed?

In all reality, many analysts agree that this is unlikely to pass through and become a reality; at least not in President Obama’s final term. With the political change in January that transformed our Congress into a Republican-controlled one, who already find too many concerns in the plan and are guaranteed to put off any legislation on it because of its Democratic origins, it’s unlikely that any current high school students will benefit from the effects right after high school. There are just, at the present, too many doubts on the plans effectiveness and the alternate options now available that could make the proposal relatively pointless. Dr. Brian C. Mitchell, founder and director of a nonprofit organization to advance higher education through “bold, sustainable” options and a writer for the Huffington Post, poses the questions that seem to be on everyone’s mind: would needs-testing be necessary? Is the plan better than a joint increase in the amount allotted by Pell Grants? Does this free-funding for community colleges seriously harm public and private four-year schools? Is there enough infrastructure across community colleges in the U.S. to support the students that wouldn’t be entirely covered with the government-subsidized program? Are transfer policies in place that will allow an easy transition from 2-year to 4-year schools? Again, at the present, there are too many possible answers to these that aren’t all sound for America.

How does this compare to the rest of the world?

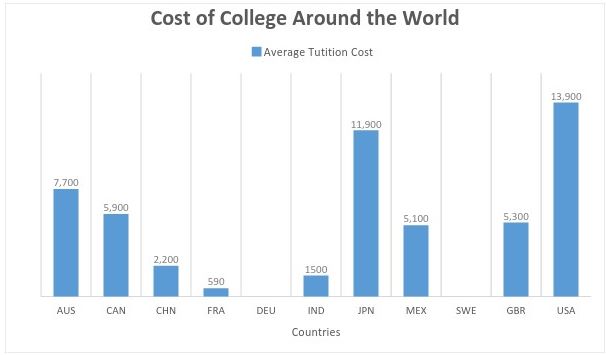

Compared to the rest of the world, the United States’ cost for college is higher than most. Coming in at an average price of about $8,300 for public schools and $28,500 for private schools, America has a higher cost than Australian ($7,700), Canadian ($5,900), Chinese ($2,200), India ($1,500), and both German and Swedish schools- coming in at $0. Right, no cost. Well, until you read the fine print: although both countries are striving to make higher education as accessible as possible, it’s only tuition that is free. Loans can still be taken out for living expenses and other costs, and it’s important to note that this only applies to citizens of the country- international students and non-citizens still pay as much as the average U.S. schooling cost. While the U.S. perhaps isn’t yet prepared to be at the standards of Sweden or Germany, it could take measures to try to cut the general college costs, and perhaps look at some effective and feasible acts to reduce students’ worries of going into debt over college loans.

In short…

All in all, “America’s College Promise” has both its benefits and drawbacks. It shows that the country is looking at improving higher-education programs, and is becoming more and more focused on making the opportunities that college offers available to all groups- regardless of economic status or household background. Though it’s undoubted that as of now the plan has questions and hiccups that will need to be sorted before coming to any Congressional vote, it is widely thought to be a step in the right direction, and with some progress and amendments to it, the initiative could potentially become a reality for all in the future.